2025: The Best and Worst Books I Read

This year sharpened my reading taste less through what I loved than through what I lost patience for. I had little tolerance for books that mistook sentimentality for insight, ambition for depth or that circled big ideas without ever committing to them. I DNF’d more readily than in past years, simply because I no longer wanted to waste time.

What consistently worked were books with clarity and confidence. I gravitated toward stories that understood systems – political, institutional or familial – and showed how individuals are shaped or broken by them. Whether dystopian, historical or contemporary, my strongest reads were willing to sit with discomfort without sanding down the edges. They didn’t rush toward catharsis or overexplain their stakes, instead they trusted the reader to keep up.

Genre mattered far less than execution. YA, westerns, memoir, horror, literary fiction – even lighter romance – were all fair game. The result is a year light on five-star reads but heavy on discernment. Not a banner reading year, but certainly a clarifying one.

Overall Favorite Read

Sunrise on the Reaping by Suzanne Collins (2025)

If you’d told me at the start of the year that my favorite novel would be the fifth book in a YA series, I would’ve called you a liar, but here we are.

With “Sunrise on the Reaping,” Suzanne Collins takes everything she meticulously built with its Hunger Games predecessors and finally lets it land with full force. Centering the story on Haymitch Abernathy turns a familiar structure into something devastatingly personal for readers.

This isn’t a story about winning, rather it’s about survival as punishment, love as liability and propaganda as a weapon. Collins leans unapologetically into the psychological horror of the Games and the exhaustion of living under constant threat – drawing unsettling parallels to our current political reality.

It’s relentless, brutal, entertaining and it doesn’t flinch.

Runners-up: “The Handmaid’s Tale” (1985) and “Lonesome Dove” (1985)

My Other Favorite Reads

The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood (1985)

Reading “The Handmaid’s Tale” after watching the series blunted some shock, but the novel remains more visceral and unsettling. Atwood’s slow-burn world-building, June’s fierce interiority and the book’s chilling relevance in today’s politics make it a necessary, uncomfortable classic to read.

The Testaments by Margaret Atwood (2019)

Expanding Gilead beyond June’s confinement, it trades claustrophobic horror for a broader, more political reckoning. Through multiple perspectives – especially a chilling, fascinating Aunt Lydia – Atwood explores power, complicity and resistance. While less brutal than its predecessor, it is a gripping sequel that deepens its legacy.

Heartwood by Amity Gaige (2025)

Blending a missing-person mystery with sharp commentary on trauma, conspiracy and public cruelty, Gaige’s novel is propelled by great characters and a superb audiobook cast. It’s a literary thriller that grips you hard while not skirting around unsettling questions about how we treat people in crisis.

Between Two Kingdoms by Suleika Jaouad (2021)

A raw, beautifully written memoir about illness, survival and living in the in-between. Jaouad captures the brutality of cancer and the disorientation of “reentry” with honesty and grace, reminding us how thin the line is between the life we plan and the one we’re given.

Lonesome Dove by Larry McMurtry (1985)

This novel earns its classic status not through mythmaking, but through intimacy. Beneath the epic cattle drive is a devastating story about loyalty, regret and love – both platonic and romantic. Lush, funny and frequently heartbreaking, it’s a western that understands the cost of dreams.

Blue Sisters by Coco Mellors (2024)

Mellors hooks you fast and then quietly devastates by exploring grief and addiction without sentimentality. Letting these deeply flawed sisters learn how to accept and endure one another is well worth the ride.

Buckeye by Patrick Ryan (2025)

Ryan turns ordinary lives – marriages, compromises and routines – into something intimate and affecting. Even when the plot is predictable, the emotional payoff is there, particularly with Margaret. By the end, these characters feel achingly real, and hard to leave behind.

Happy-Go-Lucky by David Sedaris (2022)

While still funny and caustic, this collection finds Sedaris far more honest. By leaning into grief, aging and politics without self-righteousness, he sheds the public persona and delivers some of his most vulnerable, human writing yet.

American Wife by Curtis Sittenfeld (2008)

Sittenfeld transforms a familiar political figure into an intimate, nuanced character study about marriage, power and moral compromise. It humanizes without absolving, proving the author’s rare ability to make even unappealing subjects feel real.

Honorable Mentions

The True True Story of Raja the Gullible (and His Mother) by Rabih Alameddine

A darkly funny, unexpectedly gripping portrait of a gay man aging in Beirut, shaped by family loyalty, political collapse and unresolved trauma. What looks like literary award bait refuses tidy moral lessons in favor of lived-in truth.

If Beale Street Could Talk by James Baldwin (1974)

Centered on Black love under siege, the novel pairs lyrical intimacy with quiet fury, showing how systemic injustice corrodes even the most devoted relationships. I read this in February, and I’m still thinking about it.

Your Favorite Scary Movie: How the Scream Films Rewrote the Rules of Horror by Ashley Cullins (2025)

A love letter to the “Scream” franchise made for true obsessives. Packed with behind-the-scenes insight and narrated by Ghostface himself, Cullins shows how the franchise didn’t just reinvent horror, it permanently rewired its DNA.

Broken Country by Clare Leslie Hall (2025)

A ruthless character study about grief curdling into cruelty. Hall writes deeply flawed people with such precision that even when you despise them, you can’t look away.

The Buffalo Hunter Hunter by Stephen Graham Jones (2025)

Blending vampire myth with historical reckoning, Jones reclaims the American frontier through Indigenous horror and transforms bloodlust into a metaphor for colonial violence. While messy at times, the creativity shows Jones is in a league all his own.

Lula Dean’s Little Library of Banned Books by Kirsten Miller (2024)

A sharp, funny satire of book bans and moral panic. Miller skewers fear, hypocrisy and misinformation with bite and heart, offering both liberal catharsis and a reminder that empathy and engagement still matter.

Hiroshima: The Last Witnesses by M.G. Sheftall (2024)

Unflinching accounts of the atomic bombing told through the voices of the hibakusha. Sheftall dismantles sanitized history and forces readers to confront the lasting human cost of war.

The Emperor of Gladness by Ocean Vuong (2025)

Tender, observant and frequently laugh out loud funny, Vuong proves he can add some levity without abandoning his signature melancholy. While the narrative wanders and the ending falters, the novel shines in its attention to overlooked lives and found family.

Run for the Hills by Kevin Wilson (2025)

Wilson’s high-concept absurdity actually holds this time, grounding a cross-country road trip in a surprisingly sturdy emotional core. Funny without being silly and tender without tipping into sentimentality, it’s a fresh take on family melodrama that resists easy closure – and might be his best novel yet.

Careless People: A Cautionary Tale of Power, Greed and Lost Idealism by Sarah Wynn-Williams (2025)

An unsettling insider account of power, ego and institutional failure inside Facebook. Part memoir and part exposé, it delivers plenty of jaw-dropping moments while making a sobering case for how “lethal carelessness” at the top has reshaped democracy with little accountability.

Disappointing Reads (including DNFs)

My Friends by Fredrick Backman (2025)

Despite themes of art, grief and found family, the novel leans too hard on sentimentality, repetition and juvenile humor, undercutting its emotional impact. There are flashes of insight, but they’re buried in a bloated, uneven story that never quite earns its big feelings.

Queer by William S. Burroughs (1985)

Despite its provocative context, Burroughs’ meandering, shallow narrative and exhausting self-indulgence make for a frustrating read. Moments of insight into loneliness and obsession are buried under bluster, leaving little reason to revisit – or recommend – it.

Cat’s People by Tanya Guerrero (2025, DNF)

This cozy, cat-centered neighborhood tale has an irresistible setup, but the execution never digs beneath the surface. Rotating POVs introduce a lineup of tidy archetypes rather than fully lived-in people, and the charm wears thin as the story marches toward a manufactured Big Lesson™.

No Hiding in Boise by Kim Hooper (2021)

While it tackles a heavy, timely premise Hooper never quite digs deep enough. While the rotating perspectives hint at a broader reckoning with violence and grief, the execution stays surface-level, leaning into lazy plotting over insight.

We’ll Prescribe You a Cat by Syou Ishida (2024)

After a strong opening, the stories grow repetitive and emotionally thin, turning the initial charm into an exercise in diminishing returns.

Before Your Memory Fades by Toshikazu Kawaguchi (2018, DNF)

Repeating the same café-and-ghost formula as its two predecessors, I can’t believe there are three more books in the “Before the Coffee Gets Cold” series. Even though you're transplanted to a new location, the novelty is gone, the pacing glacial and emotions are overly soft-focused.

Somewhere Beyond the Sea by TJ Klune (2024)

Earnest and well-intentioned, but weighed down by heavy-handed messaging and uneven storytelling. While its commitment to queer and trans affirmation is clear, the sequel lacks the charm, tension and narrative balance that made “The House in the Cerulean Sea” feel genuinely magical.

The Bees by Laline Paull (2014, DNF)

What should be a sharp allegory is instead an entomological fever dream. Ambitious, sure, but baffling and not worth the effort.

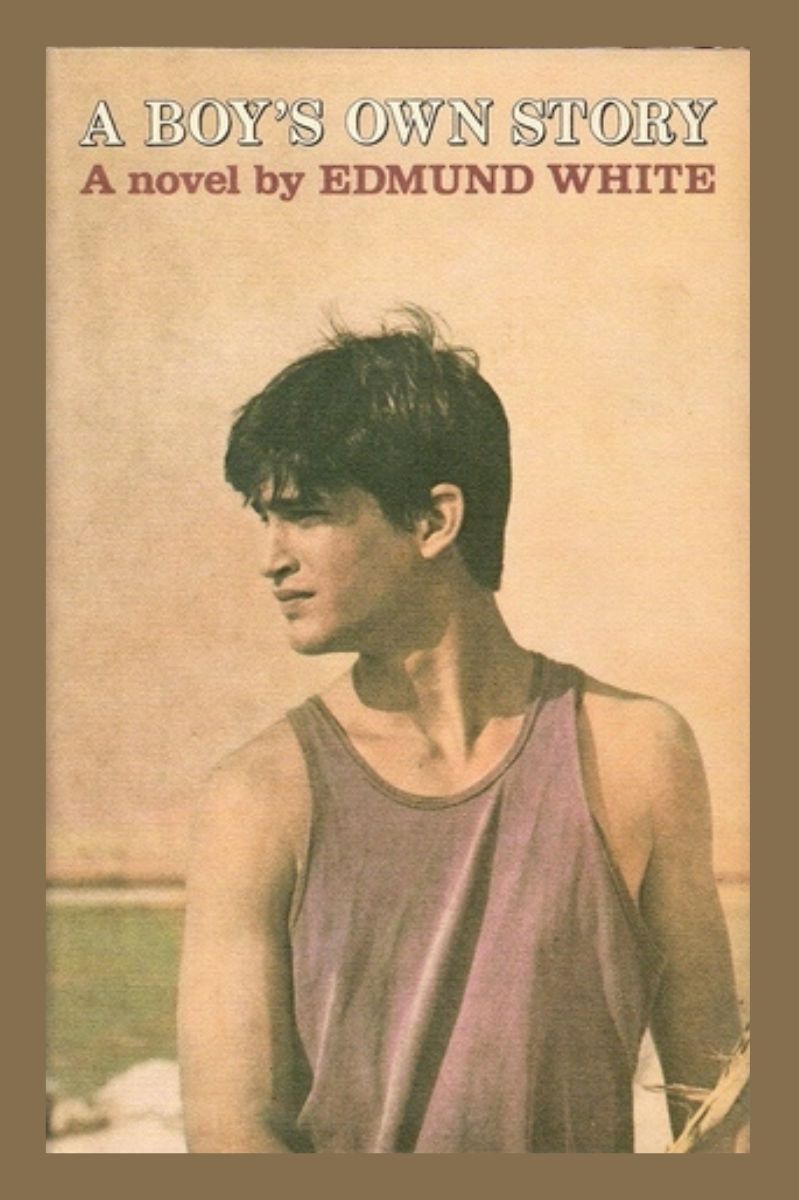

A Boy’s Own Story by Edmund White (1982, DNF)

Historically significant but deeply exhausting. Its self-regard and ornate, meandering prose drain any early promise, leaving a dated portrait of queerness that circles the same emotional ground without deepening it.