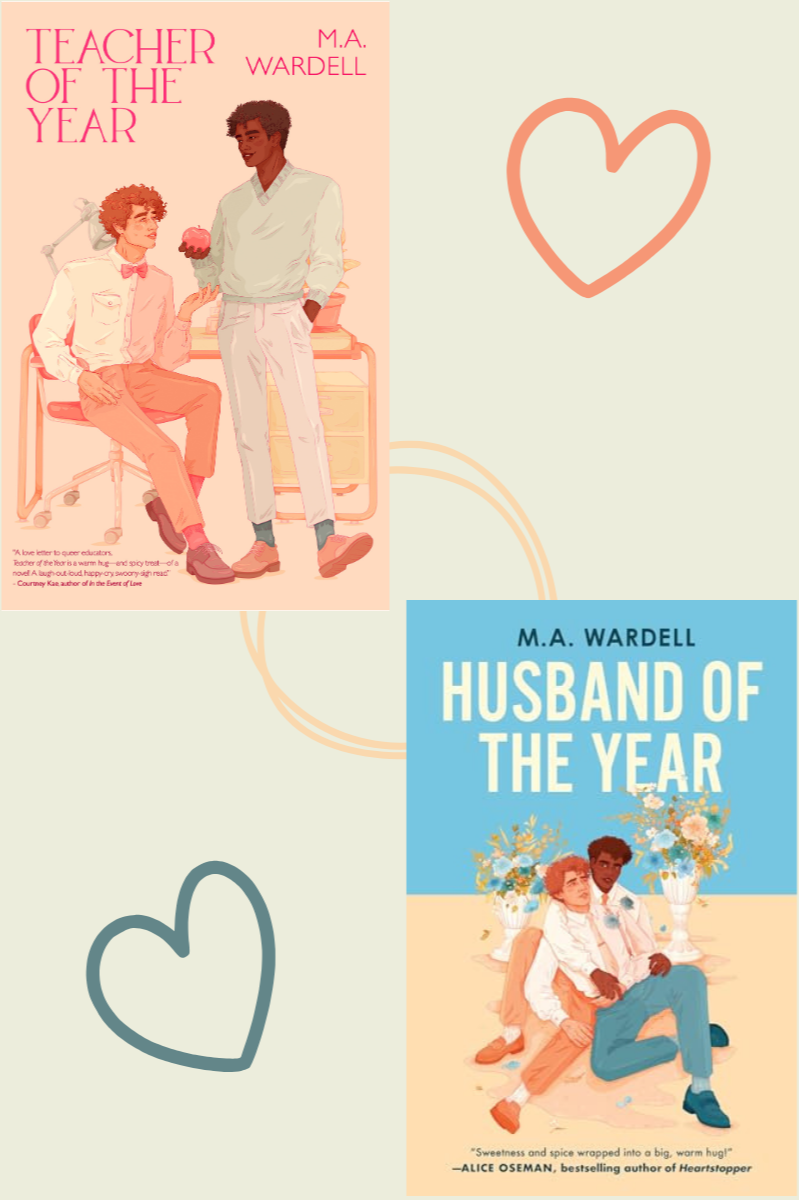

I still had a few annoyances, but they felt minor because the overall tone is charming in Marvin and Olan’s love story. This is a low-stakes romance that doesn’t pretend to be anything else. I’m still not ready to say I “read M/M romance” as a genre category, but this was a good test case of what works for me and what doesn’t.

All tagged lgbt

A Boy’s Own Story – Edmund White

This book may be a pioneer, but I don’t think it’s essential gay reading – not unless you’re interested in a very specific, very dated form of self-loathing filtered through ornate language.

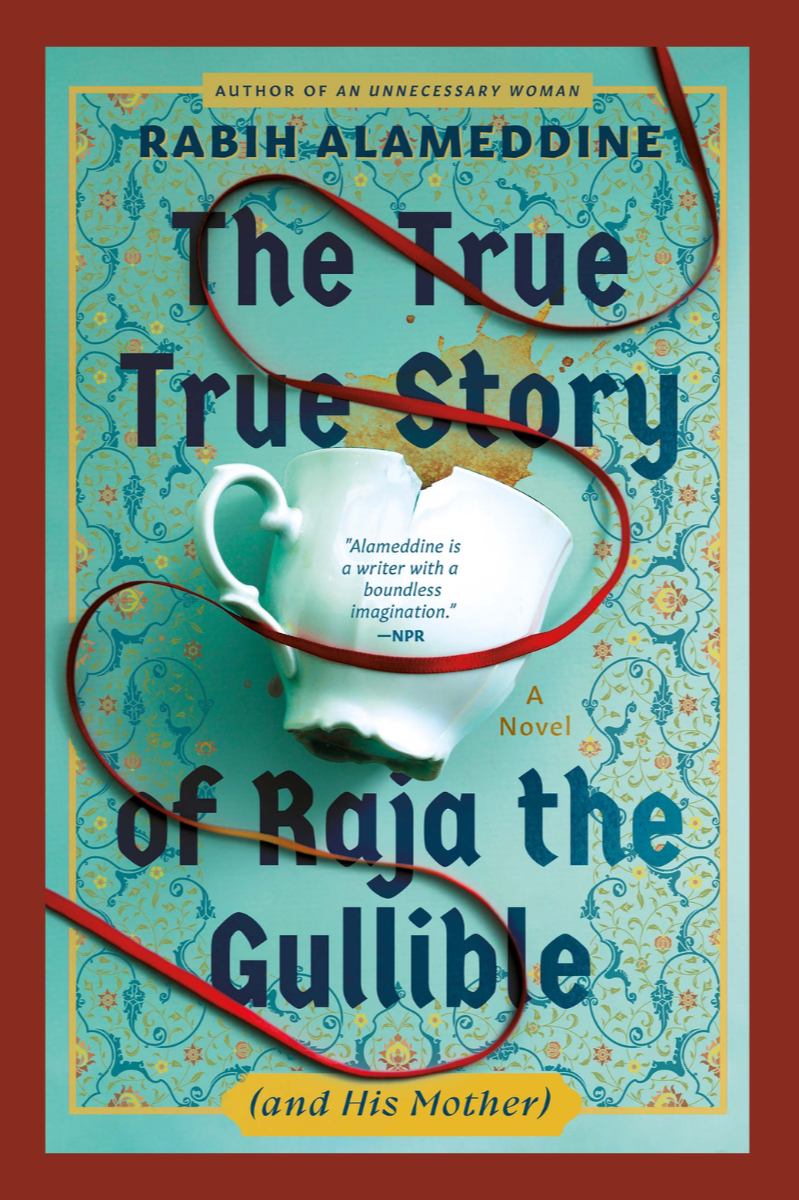

The True True Story of Raja the Gullible (and His Mother) – Rabih Alameddine

“True True” is far more entertaining than its dust-jacket suggests, and it’s absolutely worth the time. It exceeded my expectations and, like last year’s winner “James,” suggests the National Book Award isn’t afraid of honoring a novel that’s broadly appealing without being shallow.

Lucky Day – Chuck Tingle

Chuck Tingle’s “Lucky Day” blends gore, grief and cultural critique into absurdist horror that’s unsettling, chaotic and surprisingly moving.

Harriet Tubman: Live in Concert – Bob the Drag Queen

In this bold and imaginative novel, Bob the Drag Queen reimagines the legendary abolitionist as a returning historical figure determined to tell her story on stage. With help from a once-famous hip-hop producer, Tubman creates a Broadway-style musical that blends history and humor. Packed with sharp writing, emotional depth and two original songs, this audiobook is a powerful mix of speculative fiction and accessible historical storytelling.

Gaysians – Mike Curato

Set in early 2000s Seattle, “Gaysians” follows a newly out gay man who finds belonging in a tight-knit group of queer Asian friends. With bold, disco-inspired art and themes of identity, racism and resilience, Mike Curato delivers a heartfelt, funny and emotionally rich graphic novel. Perfect for fans of “Flamer” or readers seeking queer stories that center joy as much as struggle.

Atmosphere – Taylor Jenkins Reid

This is a novel about space, yes, but it’s also about constraints. What it means to want something enormous, only to realize you may have to make yourself smaller to reach it. About what it means to live within institutions that weren’t built for you.

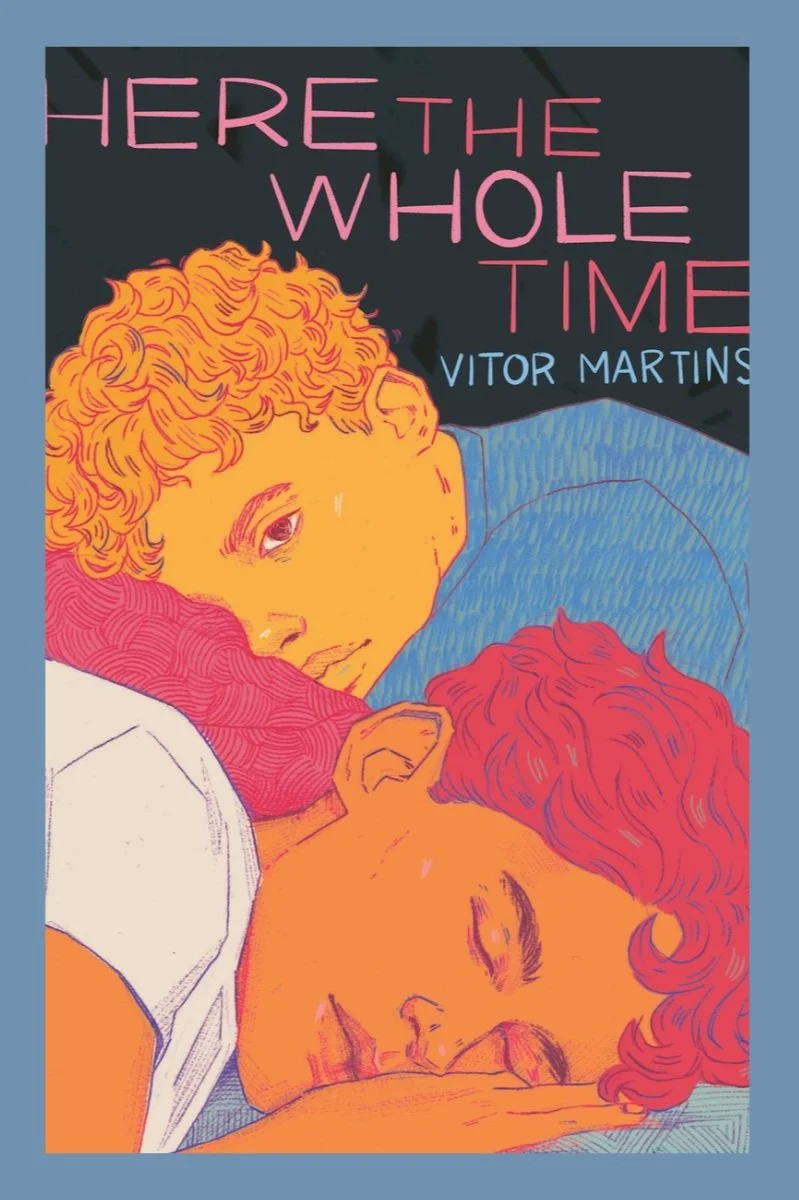

Here the Whole Time – Vitor Martins

If you’re looking for a quick, affirming read with queer representation, a strong voice and a refreshingly gentle tone, “Here” is a great way to spend an afternoon.

Bad Gays: A Homosexual History – Huw Lemmey and Ben Miller

“Bad Gays” starts with a provocative thesis: queer history is too often told through sanitized narratives of heroism and progress. What happens, Huw Lemmey and Ben Miller ask, when we shift the lens to those queer figures who were not brave icons, but bigots, fascists, abusers or simply complicated people making morally gray choices in a hostile world?

Bad Habit – Alana S. Portero

Some novels feel like memoirs, not because they’re confessional, but because they pulse with lived-in truth. “Bad Habit,” Alana S. Portero’s autofictional debut, is one of those books.

Tell Me How to Be – Neel Patel

“Tell Me How to Be” isn’t perfect. It’s sometimes overwrought, and Akash will test your sympathy, but it’s also culturally honest without pandering and willing to sit in discomfort. It shows real growth from Patel’s earlier work and enough promise to make me want to see what he does next.

Bolla – Pajtim Statovci

“Bolla” isn’t a book you’ll want to live in for long. It offers no comfort, no catharsis, only the slow, painful truth that repression – personal or political – rarely leaves survivors.

Somewhere Beyond the Sea – TJ Klune

“Somewhere Beyond the Sea” wants to be a beacon, but it ends up an echo of what made “The House in the Cerulean Sea” so beloved. It wants to offer the inclusive magic Rowling won’t, and for some readers, that alone may be enough. But intent doesn’t equal impact. The message may still shine through, but the journey is far less enchanting than before.

Queer – William S. Burroughs

This novella has solidified my disinterest in Burroughs and, perhaps, in the Beat Generation as a whole. As for the film adaptation, I’ll take a pass – I’ve given this story enough of my time.

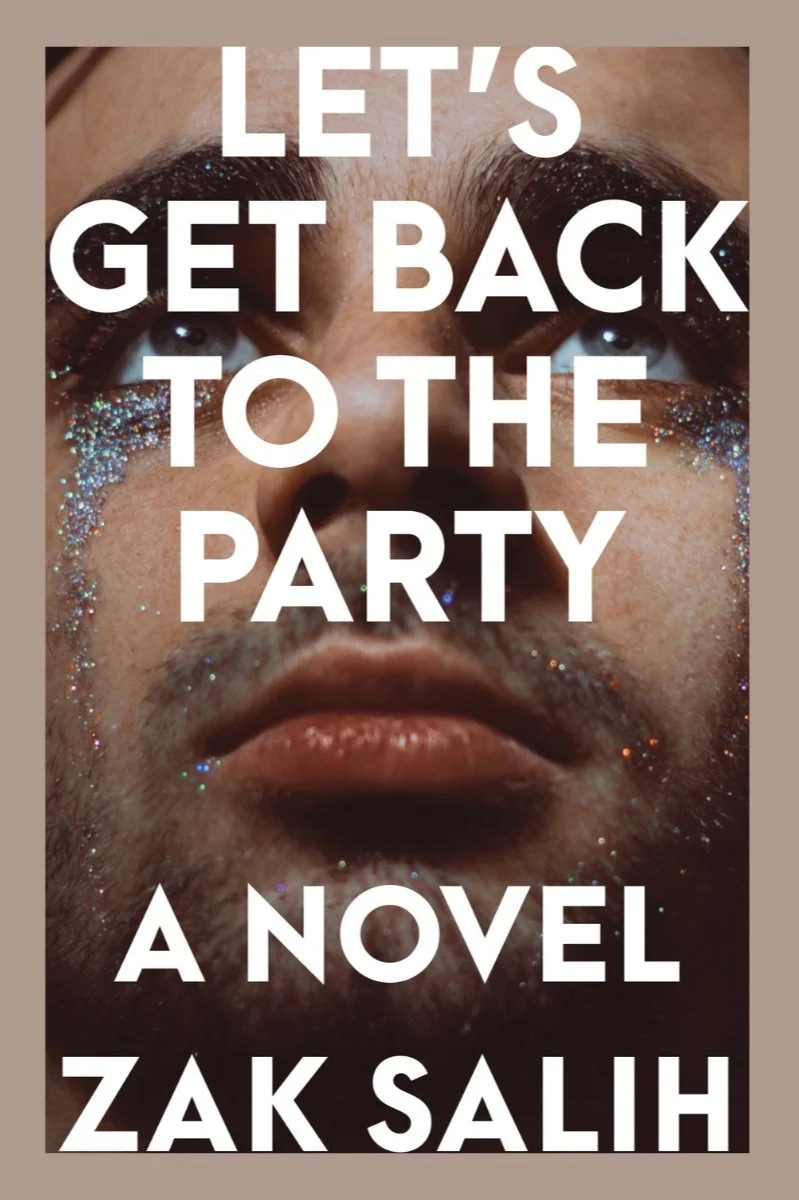

Let’s Get Back to the Party – Zak Salih

From the Obergefell ruling to the Pulse nightclub massacre, “Party” captures the emotional and political climate of a pivotal year for the LGBTQ+ community. The novel questions the expectations placed on modern gay men, contrasts different generational perspectives and resists a tidy resolution, embodying the complexity and contradictions of queer existence in a post-modern world.

Isaac’s Song – Daniel Black

Daniel Black’s “Isaac’s Song” is less a sequel to “Don’t Cry for Me” than a companion piece, giving Isaac’s long-awaited perspective on his relationship with his father, Jacob. While “Cry” was a reckoning told through a dying father’s letters, “Song” is a son’s introspective journey through memory, contradiction and generational trauma.

Private Rites – Julia Armfield

Though the prose remains lush, her reliance on symbolism and Shakespearean allusions requires a level of patience and literary devotion this novel didn’t earn. For those well-versed in “King Lear” and drawn to dense, slow-burn literary fiction, there may be more to appreciate.

Lawn Boy – Jonathan Evison

Jonathan Evison’s “Lawn Boy” attempts to tackle social inequality with humor and heart, but its execution falters. While the book has been challenged for fleeting references to sex and gender identity, these objections feel exaggerated. The real discomfort lies in its critique of systemic barriers that make stability and success elusive for marginalized communities—a critique that some may find hard to swallow.

The Lie: A Memoir of Two Marriages, Catfishing & Coming Out – William Dameron

For readers interested in a nuanced look at coming out later in life, particularly in the mid-2000s – a time when acceptance was growing but still fraught with homophobia and fears of ostracism – “The Lie” offers an authentic, if imperfect, reflection.

Small Rain – Garth Greenwell

Garth Greenwell’s “Small Rain” explores the isolation and unraveling of self that so many of us endured during the first COVID-19 summer. His unnamed protagonist experiences this in a way that’s magnified tenfold, as he is confined to a hospital room with a potentially fatal diagnosis: an aortic dissection. The fact he survived such low odds and remains coherent adds an underlying tension to every encounter. He is suspended in a liminal state, living on what feels like borrowed time.